Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States

by Howard Chandler Christy

Artist’s Biography

Howard Chandler Christy was born in Morgan County, Ohio on January 10, 1873, into a family that traced its lineage back to the Mayflower Compact. He attended art school in New York during the 1890s, and by age 25 was painting live military illustrations of the Spanish-American War for several well-known magazines. He became especially famous for his “The Soldier’s Dream” renditions of women. “The Dream” woman became his prototype for “The Christy Girl,” portrayed in his 1900-1921 paintings of a charming, beautiful, educated and emancipated woman. His second wife, Nancy Palmer, was his model for many of the “Christy Girl” paintings.

World War I also elicited patriotic sympathy from Christy: He painted over 40 posters for recruitment, bond sales, victory liberty loans, and other efforts on behalf of the war. His 1919 Victory Liberty Loan poster, for example, portrays a “Christy Girl” proclaiming support for “Americans All,” next to an “Honor Roll” listing fourteen of the names on a casualty list sent by General Pershing: “Du Bois, Smith, O’Brien, Cejka, Haucke, Pappandrikopolous, Andrassi, Villotto, Levy, Turovich, Kowalski, Chriczanevicz, Knutson, and Gonzales. “Americans All,” indeed, both then and now!

During the 1920s, Christy turned from magazine illustrations and patriotic themes to personal portraiture. He became associated with the celebrity circle and painted a wide range of people from Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt to Benito Mussolini. In the mid-1930s, he received several invitations to interpret critical historical events, and these led in 1940 to the unveiling of his most famous painting, “The Signing of the Constitution.” He also painted a number of religiously oriented posters on behalf of the World War II effort. Christy died in New York in 1952 at the age of 80.

The Painting

History

Howard Chandler Christy’s painting of the Signing of the Constitution on September 17, 1787 is conventionally acclaimed as the best single picture ever created of the American Founding. In contrast to Barry Faulkner’s nearly contemporaneous version of the Signing in the National Archives, which portrays 25 delegates, three of whom declined to sign and three more who left early, standing in an ancient Roman setting, Christy’s painting makes a great effort at historical authenticity. It also engages in political interpretation, captures the Convention at work, and brings the American Founders to life.

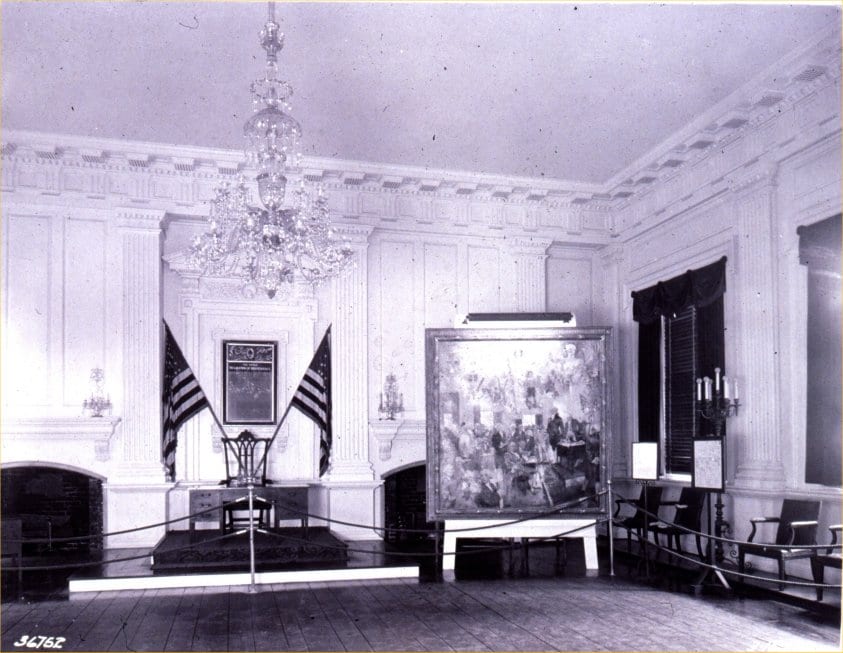

Christy developed his idea of the signing scene inside Independence Hall while working on an earlier painting. This was a five by seven foot work called “We the People,” portraying the spirit of Liberty, Peace, and Justice presiding over the founders as they affixed signatures to the finished Constitution. Christy completed this painting in 1937 and offered it, as his gift to the American people, to the Commission on the Sesquicentennial of the Signing of the Constitution. He had spent two years working on it inside Independence Hall itself. At the time, Independence Hall served as a collection of Founding material rather than as a replica of the original building. Portraits of the Founders hung from the walls, undoubtedly inspiring Christy’s attention to historical accuracy as he painted each founder. Sources also suggest that he did a lot of his preliminary sketches in Independence Hall during the month of September, in order to replicate the lighting of the room at that time of year.

Later, in preparation for the bicentennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1976, the interior of Independence Hall was restored to its original condition. The photographs on the wall were removed and placed in the Second Bank in Philadelphia or the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D. C. But at the time of the Sesquicentennial of the Constitution, Christy’s painting was part of the display at Independence Hall, and his “We the People” draft of what would become a monumental painting of the Signing is clearly inspired by the presence of the Framers looking down on him from on high.

Christy’s Independence Hall “We the People” painting went over so well that Congress and President Roosevelt, in Spring 1939, invited him to produce a twenty by thirty-foot version that would be hung in the Capitol. The completed painting was unveiled in the Rotunda of the Capitol in May 1940.

Philip Cenci’s Recollection of the Christy Painting

My entire life I have heard the story about this painting from my father who was a witness to the entire process from planning to creation of this painting. As a boy of sixteen, he was an apprentice in The Period Shop which was a woodworking shop on Second Avenue that was run by a combination of German and Italian immigrant artisans…who…made furniture for New York City’s millionaires. My grandfather was an artist who immigrated from Florence and would be contracted by The Period Shop to carve artwork in wood for their furniture. Through this shop and through art contacts, my grandfather knew and worked for Azeglio Pancani.

My father has retold the story of Pancani[AB7] and Christy sitting in their apartment on Second Avenue with his father going over sketches for the frame.… The design of the frame was Pancani’s, the design of the eagle was my grandfather’s. My father remembers him arguing for asymmetry of the wingspan of the eagle because an eagle launches ‘into the wind when on the attack’ and it would not appear symmetrical in nature. My father spent countless hours doing the fine sanding of the wood after it had been carved. We still have a smaller model of the eagle that was done by my grandfather.

Also, some sources claim that the painting was done at the Navy Yard in Brooklyn, but my father clearly disputes that because he delivered the frame to Chandler Christy’s studio on Central Park West where he had a two-story suite. He actually saw Christy painting a scene of this painting there. The frame was finished at the shop on Second Avenue and then delivered to Christy. My father’s older brother made the trip to Washington to assemble the frame and install it in Washington.

Time Magazine, September 29, 1941

One of the eternal problems of art rose last week in the U.S. Capitol: the problem of hanging a historical picture. Since historical pictures cover a lot of space, Capitol Architect David Lynn and a special crew of workmen equipped with pulleys, rollers and winches clambered up and down the Capitol’s stairways and through its second-story windows like a swarm of hungry ants tugging at a dead grasshopper. First they removed Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s modest mural, First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, size 9 by 14, from its 63-year-old place above the east Grand Stairway just off the Capitol’s lower chamber. Then to the wall they hoisted a new historical whopper: Howard Chandler Christy’s Signing of the United States Constitution, size 20 by 30.

Interpretations of the Painting

Interpreting an interpretation is a perilous exercise. Nevertheless, Christy’s painting is so vital to the celebration of the American Founding that I owe the contemporary viewer a few thoughts on what Christy is attempting to portray in this commemorative painting:

- Christy shows the room illuminated by light entering windows framed by heavy curtains. During the proceedings of the Convention, these curtains were drawn in order to preserve the agreement on secrecy. The Founders worked in dim candlelight, trying to find a solution to the problem of how best to frame a republican government. Now that the solution has been found, we can move from darkness to light.

- Christy made a sketch of the painting that assigns a number to each of the delegates. This enumeration is available to the public when they view the painting. The first seven on Christy’s list are, with the exception of Franklin, all Federalists who favor strong central government: Washington, Franklin, Madison, Hamilton, G Morris, R. Morris, and James Wilson. They are separated out from their state delegations and are displayed as independent heroes at the Convention. Put differently, Christy places the supporters of a strong general government in perhaps larger than life positions. Madison is seated alone at a table near the podium surrounded by crumpled and uncrumpled notes. Perhaps this symbolizes Madison as the “Notetaker” of the Convention. Washington, surrounded by light, and Franklin, surrounded by books and cane in hand, are there not for what they did at the Convention, but for their heroic position in American life, something that in Christy’s time was very much portrayed in the literature about the American Founding.

- R. Morris is not there for his contribution at the Convention—he never spoke—but because he was the financier of the American Revolution. Christy signals that his actions of 1776 were critical to the deliberations of 1787. Madison, Hamilton, G. Morris, and Wilson are clearly the architects of the Constitution as far as Christy is concerned, and this portrait certainly captures a central sense of American self-understanding. But what Hamilton could possibly be whispering to Franklin, both center stage in the painting, challenges the imagination. They rarely spoke; in fact, Hamilton was gone half the time from the Convention and Franklin asked Wilson to read an address to the convention on his behalf. One wonders what Christy had in mind. I doubt it had anything to do with the politics of the Convention.

- The remaining delegates are seated or standing inconspicuously, for the most part, with their state delegations. But there is a peculiarity that needs explanation. Why are the three delegates from South Carolina raising their arms in apparent salute to Washington, who stands taller than anyone in the room? They seem to be gesturing their thanks and respect to the General. But there is another very practical explanation. Christy was painting the Founders from the official paintings hanging in Independence Hall. There was no verified official portrait in the 1930s of Pierce Butler of South Carolina or Thomas Fitzsimmons of Pennsylvania, so Christy has their faces hidden by the raised arms of the South Carolina delegation. There is also a blur of faces in the corner to the right of Washington. Christy has been very creative: he has placed John Dickinson, whom Christy has listed as the thirty-eighth signer—who actually wasn’t there at the signing because of health reasons, but who had George Read sign on his behalf—in front of the face of Jacob Broom, whom Christy lists as the thirty ninth and last of the signers. There was no official portrait of Broom available in the 1930s.

- At the very center of the painting is William Jackson. He obviously is critical in Christy’s rendition; Christy incorrectly lists Jackson as the fortieth and last of the “signers.” Jackson did not sign the Constitution; he recorded the resolutions and votes during the convention. Christy portrays him as important because he recorded the deliberations.

- There is only one delegation seated at a table—even though all delegations in fact had their own table at the Convention—and that is the Connecticut delegation. There are pieces of crumpled paper on the floor next to Sherman and Johnson. This is in contrast to the other table where Madison looks rather pleased with himself. Sherman and Johnson were the authors of the Connecticut Compromise that settled the issue of representation and they worked long and hard for the compromise that ensures that the people are represented in the House and the States are represented in the Senate. It is unclear whether Christy is praising the Connecticut delegation, criticizing them, or indicating their only partial satisfaction with the outcome.

- I’m not sure why Christy gives the honor of signing to the North Carolina delegation, especially since he has given prominence to seven individual members. My best hunch is this: if it weren’t for the Connecticut delegation, the North Carolina delegation wouldn’t have come around to the Connecticut Compromise, and without their support, we wouldn’t have a Constitution, whatever the seven movers and shakers wanted.

- Behind Washington, Christy has a painting of four flags and a drum. What these symbols represent is, of course, also open to interpretation. One of the three flags is clearly the one supposedly sewn by Betsy Ross in 1776 at the request of Washington; it is the flag that has inspired all the other flags that have been adopted by the country. The other three flags and drum are more difficult to identify, but they probably represent the transition from the battle with the British to the discussions taking place in the room: a movement from revolution to constitution.

The Delegates

73 delegates were appointed to the Constitutional Convention.

18 declined their appointments: Richard Henry Lee (Virginia), Thomas Nelson (Virginia), Patrick Henry (Virginia), Abraham Clark (New Jersey), John Neilson (New Jersey), Richard Caswell (North Carolina), Willie Jones (North Carolina), George Watson (Georgia), Nathaniel Pendleton (Georgia), Henry Laurens (South Carolina), Francis Dana (Massachusetts), Gabriel Duvall (Maryland), Robert Hansen Harrison (Maryland), Thomas Stone (Maryland), Charles Caroll (Maryland), Thomas Sim Lee (Maryland), John Pickering (New Hampshire), and Benjamin West (New Hampshire).

Only 39 of the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention are pictured in the Christy painting. Not included are the 3 delegates who did not sign the Constitution: Edmund J. Randolph (Virginia), George Mason (Virginia), and Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts). Also not included are the 13 delegates who left the convention early: Oliver Ellsworth (Connecticut), William Houstoun (Georgia), William L. Pierce (Georgia), Luther Martin (Maryland), John F. Mercer (Maryland), Caleb Strong (Massachusetts), William C. Houston (New Jersey), John Lansing, Jr. (New York), Robert Yates (New York), William R. Davie (North Carolina), Alexander Martin (North Carolina), James McClurg (Virginia), and George Wythe (Virginia).

Author’s Note

This account of the work of Howard Chandler Christy is based in large part on material available in the National Archives in Washington D.C. and The Special Collections and College Archives at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania where the Christy Papers are housed. I also want to thank Dennis L. Boyles for permission to reprint the letter from Christy to Cook as well as the Historic Statement that came with it. Thanks to James Philip Head for Christy’s invitee list for unveiling of the painting. And thanks to Philip Cenci for sharing his story about his father and grandfather. The thoughts on the painting are my own.